Doing Things That Don't Scale: What Start-Ups Can Teach Parents About Education

Paul Graham, the founder of Y Combinator, the premier start-up accelerator in Silicon Valley, advises the companies that go through the program to "do things that don't scale" if they want to improve their chances of becoming breakout successes ("unicorns," in Valley parlance). The problem that Graham diagnoses is the extreme and universal difficulty of kick-starting the growth of an early-stage company, and he proposes a simple solution – that the founders of these companies do whatever it takes, brute force, to acquire and delight their initial cohort of customers. These activities may not be sustainable once a company has thousands of customers, but when a company is just getting started, it has the luxury of being able to serve the customer in the best way possible regardless of how well those activities will work at scale. The value to the customer is obvious. It is always going to be more appealing to receive white-glove service and an offering tailored for one's individual needs than to be forced to accept whatever is on offer from a faceless behemoth.

The basic principle – that small and individualized is better than big and one-size-fits-all – is commonplace. Small-batch distillers, indie bookstores offering personalized recommendations, fancy restaurants where the chef brings out the food directly to the diner, and farmers' markets all operate on it. Recent years have seen vendors of this type proliferate in reaction to the homogeneity of established brands, especially in the more stylish neighborhoods of major cities (Williamsburg, the Mission, East Nashville, etc.) Education, however, is one area that has lagged behind this trend.

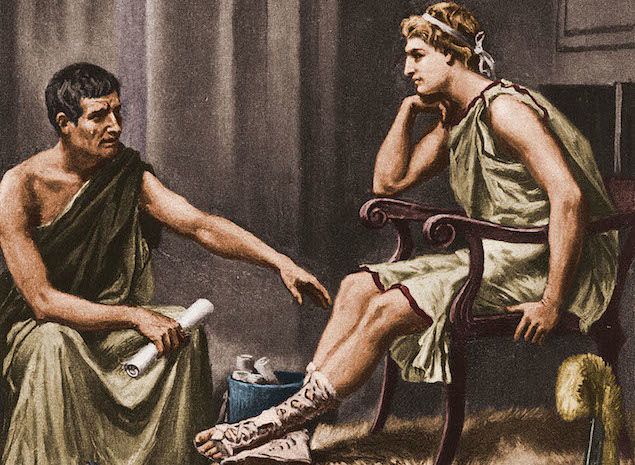

For much of history, one could describe essentially all education as "small batch." During most of that time, of course, very few people received any academic education, so balancing supply and demand was not a problem. A small number of schools and universities existed for training future churchmen and bureaucrats, and private tutors provided the children of aristocrats with individual instruction. (Michel de Montaigne's father hired a tutor to speak nothing but Latin to the boy and forbade the use of any other tongue by any member of the family in his presence). It was an education system designed for quality over quantity. It didn't scale – not every child could learn like Montaigne – but as anyone who has pondered the wisdom of the Essais can attest, it worked.

The advent of mass education in the twentieth century opened up tremendous opportunities for children to open their minds to learning regardless of the material circumstances into which they were born. This revolution in the accessibility of education also drove an economic revolution as decades of rapid growth in both the industrial and information economies have led to extraordinary levels of prosperity in the developed world and the lifting of billions of people out of poverty in developing regions.

The education system that delivered this revolution was built to deliver education at scale, and it does so through its primary tool, the school. The school is to education as Jeremy Bentham's idea of utilitarianism is to morality – its goal is to deliver the greatest good to the greatest number. The differences between public and private schools are not significant in this respect – private schools may have slightly smaller class sizes, but the basic models of both are essentially the same. This is consistent with the fact that students' educational outcomes, when adjusted for their families' socioeconomic status, are indistinguishable regardless of whether they went to public or private schools.

To achieve a distinctive outcome, one must take a distinctive approach, and that means doing things that don't scale. Like the start-up founder who wants to build the next technology unicorn, this means that parents with exceptional aspirations for their children must roll up their own sleeves and take an active role in teaching their children. "Education" is more than just "schooling." Even in the unfathomably rich families that can hire governesses with advanced degrees in mathematics or Latinists like the one found by Montaigne's father, the reality is that there is no true substitute for the involvement of the parents themselves. Spend an hour talking to teachers at the most elite and expensive private schools in New York City, and you will hear plenty of stories of students without instrinsic motivation, who lack the grit to conquer hard problems, and whose dysfunctional relationships with their families distract them from their learning.

So is the situation hopeless if parents are not themselves academics? Far from it. One aspect of education that does scale well is the book, and we are fortunate that many of the greatest thinkers and educators in history have passed their work down to us in printed form. These resources are at the ready for parents to use in cultivating a rich intellectual life for their children, with the only financial cost being, as Matt Damon observed in Good Will Hunting, a few dollars in late fines at the public library. The real commitment that they ask is time.

Furthermore, just as the "sage on a stage" model of teaching is rightly denigrated for its passivity, the role of the tutor should not be merely to impart knowledge, but rather to awaken the love of learning through a mutual pursuit of the truth. A parent need not be a Latinist to embark on a shared study of Virgil with his child. A purposeful visit to an art museum with a reference book in tow and a curious hand raised with questions for the docent will work wonders. Successful start-up founders devote their lives, day and night, to their companies because they, not their investors, employees, advisors, or partners, bear ultimate responsibility for whether their ventures will thrive or wither. For children to flourish, parents must do the same.

Comments ()